Describe what happens when you type a URL into your browser and press Enter.

Solution

We’ll go through a very general and high-level overview of how requests are made, comprised of the following parts:

- DNS Lookup

- HTTP Request

- Server Handler

- Rendering

DNS Lookup

First, the URL, or domain name, must be converted into an IP address that the browser can use to send an HTTP request. Each domain name is associated with an IP address, and if the pair has not been saved in the browser’s cache, then most browsers will ask the OS to look up (or resolve) the domain for it.

Here, operating systems usually have default DNS nameservers that it can ask to lookup. These DNS servers are essentially huge lookup tables. If an entry is not found in these nameservers, then it may query other to see if it exists there, and forward the results (and store them in its own cache).

To learn more:

HTTP Request

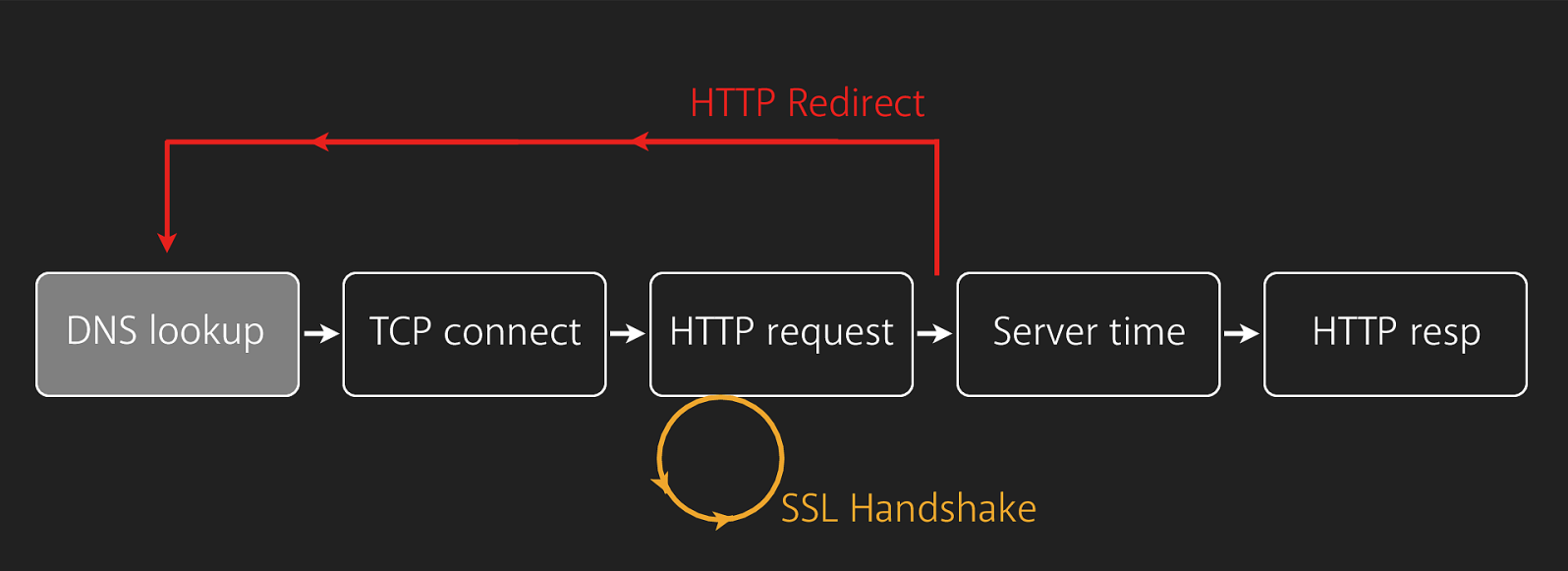

Once the browser has the correct IP address, it then sends an HTTP GET request to that IP.

The HTTP request must go through many networking layers (for example SSL if it’s encrypted). These layers generally serve to protect the integrity of the data and do error correction. For example, the TCP layer handles reliability of the data and orderedness. If packets underneath the TCP layer are corrupted (detected via checksum), the protocol dictates that the request must be resent. If packets arrive in the wrong order, it will reorder them.

But basically, in the end, the server will receive a request from the client at the URL specified, along with metadata in the headers and cookies.

To learn more:

Server Handler

Now the request has been received by some server. Popular server engines are nginx and Apache. What these servers do is handle it accordingly. If the website is static, for example, the server can server a file from the local file system. More often, though, the request is forwarded to an application running on a web framework such as Django or Ruby on Rails.

What these applications do is eventually return a response to the request, but sometimes it may have to perform some logic to serve it. For example, if you’re on Facebook, their servers will parse the request, see that you are logged in, and query their databases and get the data for your Facebook Feed.

Rendering

Now your browser should have gotten a response to its request, usually in the form of HTML and CSS. HTML and CSS are markup languages that your browser can interpret to load content and style the page. Rendering and laying out HTML/CSS is a very tricky process, and rendering engines have to be very flexible so that an unclosed tag, for example, doesn’t crash the page.

The request might also ask to load more resources, such as images, stylesheets, or JavaScript. This makes more requests, and JavaScript may also be used to dynamically alter the page and make requests to the backend. For example, the button on this page uses Javascript to show and hide the solution.

More and more, web applications these days simply load a bare page containing a JavaScript bundle, which, once executed, fetches content from APIs. The JavaScript application then manipulates the DOM to add the content it loaded.

Resources:

Conclusion

This is only a brief overview of a possible answer to this question. Any of these topics merit a book-length treatment! Generally, in an interview, this question is asked to see if you’re familiar with the web, how it works, and your mental model of it.

It’s impossible to know the whole stack in-depth, so sometimes interviewers like to explore a particular aspect of the stack that they are interested in, or you can go into more in depth about a part of the stack that you’re more knowledgeable about. In any case, it’s interviewers will reward coherent explanations because your interviewers will be working with you and want to see how you think.